In October, 2023, my wife Karen and I took a two-week birding trek through the Andes and lowlands of Bolivia. We had retained our friend and guide Emiliano (Indio) to guide us. As usual, our principal objectives were to see the birdlife of as many Bolivian habitats as possible during our short stay and to assess the biodiversity resources and corresponding threats by habitat type. These objectives were hampered by a number of factors, including a prolonged drought in most of the country, a backdrop of civil unrest, and a high incidence of fires during the last week of our trip.

Our transect (see accompanying route map) included the high Andes grasslands north of La Paz, the effective capital, and surrounding Lake Titicaca, the largest natural body of water in South America and the highest large lake in the world; the spectacular Yungas forests of middle elevations, dry inter-Andean valleys near Cochabamba, and seasonally flooded grasslands and savannahs in the lowlands of the Beni Department. In the time we had, we were unable to access two important habitat types: the chaco forests in the southern provinces (“departments”) and the Amazonian forests that blanket the far north and northeast of the country.

Our destinations mapped out with e-bird below:

Meet our Bolivia guide and amigo Indio in the video below:

Background Facts

Bolivia is a large landlocked country in southern South America, bordered by Chile on the west, Peru on the north, Argentina on the south, and Brazil and Paraguay on the east. The current borders of the country have resulted from wars with neighboring countries, mostly resulting in reduced boundaries for Bolivia (and in particular the absence of seacoast access). There is a striking contrast in natural habitats created by the country’s diverse geography. The highest mountains border Chile on the west, with the Andes running the length of the country. The land slopes from the highest mountain peaks eastward to the Amazonian lowlands, with most of the country lying in the eastern lowlands. Much of the population is centered in the major cities located either in dry inter-Andean valleys or in and around the economic engine of Santa Cruz de la Sierra in the large eastern department of Santa Cruz.

Bolivia’s economy has long been fueled by mining revenues. For centuries silver, tin and gold dominated exports; now its vast stores of lithium in the south of the country will join the mix. Since the 1980s, commercial agriculture in the lowlands has provided steady export revenue from foreign markets. Unlike most African countries, such as Angola, Bolivia does not suffer from exponential population growth. In 2023, the United Nations estimates the population of Bolivia to be 12.4 million people. The population doubling rate projection is 48 years. Nonetheless, Bolivia is one of the poorest countries in South America. With the support of the national government, the country has experienced widespread and vast internal economic migration from highland communities to its major cities and the lowlands of the east. Particularly in the east, this trend has resulted in invasion of the community lands of other indigenous peoples.

Political strife is a way of life in Bolivia. With the largest population of indigenous people in South America – estimated at 41% - social inequality has resulted in frequent, sometimes violent revolts against national and regional governments run by elites of European descent. (The largest groups of indigenous peoples in Bolivia are the Aymara and the Quechua of the highlands, and the Guarani of the lowlands.) In 2005, the first indigenous president was elected – Evo Morales. Morales campaigned on promises to achieve land reform. Following his election, the government undertook broad nationalization of foreign assets and established a program of returning lands to control of indigenous communities. This dynamic is still at work and, as will be seen, poses significant challenges to conservation of Bolivia’s biological resources.

Puna photo highlights below:

Video of Santa Cruz in Sunlight below:

Biodiversity Resources in Bolivia and Threats to Preservation

Habitats. Because of its varied geography and climate, Bolivia’s forests are among the most biodiverse on the continent. According to some estimates, 49 % of the land is still forested. Bolivia ranks 6th in the number of bird species among the world’s countries, hosting nearly 1500 within its borders. Because agricultural production was not mechanized on a broad scale until the 1980s, the rate of deforestation in Bolivia was much lower than that of neighboring countries like Brazil. Things have since changed. Mainly because of events in the Amazon basin and the chiquitania forest in Santa Cruz Department, most prominently increased soy production, Bolivia’s deforestation rate in 2022 was the third highest in the world. In the preceding 8 years, deforestation in Bolivia increased by 259%.

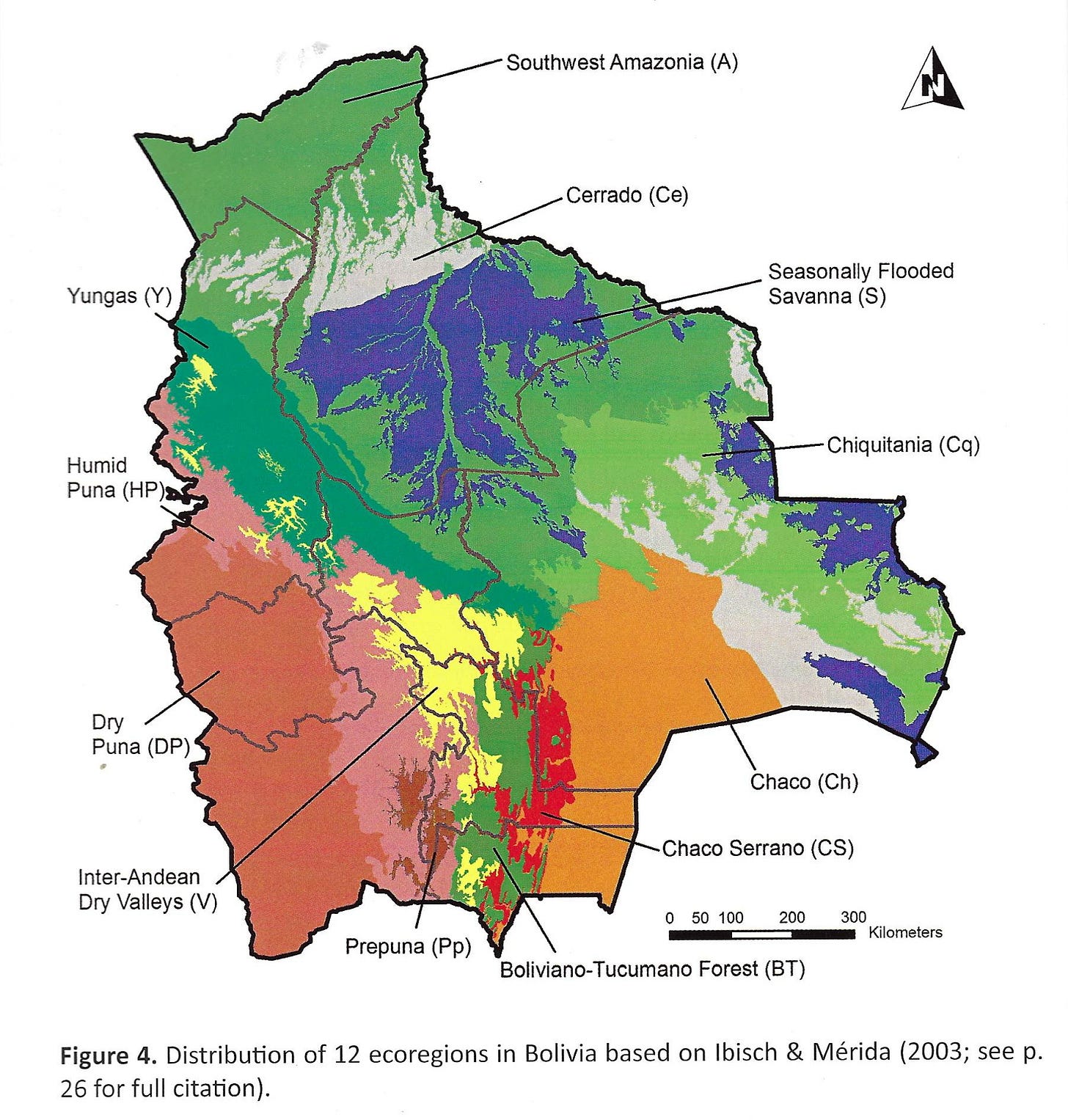

In order to understand the ongoing threats to biodiversity in Bolivia, it is important to distinguish its many types of habitats. The accompanying table and map show the various types of vegetative communities which are conditioned both by altitude, temperature and rainfall. The highlands in the west, cultivated for thousands of years by pre-Incan civilizations, are blanketed by grasslands called “puna” and may be divided into dry and wet components. (There is of course an intergradation between these habitat types, and it is not always possible to classify puna by its moisture content, particularly in the context of the prolonged drought that is affecting the highlands.)

The middle elevations of the Andes are occupied on the eastern slopes by broadleaf and fern forests known as the Yungas in the north of the country and Bolivianio-Tucumano forest in the south-central part of the country (more common in the Andes of northwestern Argentina). Depending on rainfall patterns, Yungas forests at higher elevations support “cloud foress” that is the richest in bird life. (Some authorities limit the term to forests in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.) Cloud forests often are covered in fog and mist for much of the day. Epiphytes grow in abundance. Mixed flocks of insectivorous birds move through the canopy and middle levels of these forests in collective foraging strategies. Such flocks can contain scores of different species.

Amazonian vegetation meets the Yungas forests on the lower, wetter slopes of the mountains in the north, stretching from the extensive stands of tall tropical rainforest of the Southwest Amazon and extending to the foothills of the Andes, resulting in a mixed avifauna. Inter-Andean valleys, where most large cities are located, contain drier, deciduous vegetation, often approaching desert-like conditions. The valley floors of this region have long been converted to agriculture, but good habitat still persists on the adjacent slopes.

The eastern lowlands contain several forest types. Surrounding Santa Cruz and further to the east, chiquitania forest consists of lowland tropical vegetation, with trees being of medium height and stature. Seasonally flooded grasslands form broad “llanos” between the Amazon and other lowland areas. Forest patches consist of “islands” of trees or gallery forests along river corridors. The large areas adjacent to the Amazon, known as “cerrado,” consist of grasslands, shrubs, and short trees. Typically, these areas are not subject to inundation. As with Andean forest regimes, lowland habitats intergrade with one another. (Other biomes exist in Bolivia, but our travels were confined to an east-west transect in the north central part of the country.)

Video of the High Andean Lake, Puna Highlands below:

Puna Highlands. Before our birding tour began, we spent a day exploring the ruins of Tiwanaku, an important center for the Andean civilization that preceded Inca rule. The site, which lies east of Lake Titicaca, occupies a relatively flat grassland valley at an elevation of about 13,000 feet. At the height of Tiwanakus’ dominion, it is believed that the area contained a population of as many as a million people. These communities were sustained by intensive agriculture methods involving a unique system of irrigation. The tradition was lost over time. Rocky fields, most of which lie fallow, contain wisps of short bunch grasses that cannot compare with the lusher grasslands of the higher punas. The abandonment of these overused agricultural valleys has not resulted in the recovery of grassland habitats, a fact to remember when evaluating whether the traditional practices of highland communities should be sustained under programs to conserve biodiversity resources in middle elevations.

Video of High Andean Grassland with Canastero below:

Video of Indio discussing the Puna Transition Zone:

Our tour began in the puna highlands north of La Paz at an elevation of 16,000 feet. At this altitude, one walks extremely slowly up and down the grass-covered hills. The highlands also contain many lakes that support waterfowl and birds of the shore. The area we visited first, a national park, contained a carpet of bogs, which due to the drought, had little water. Bogs are exploited by local communities, which remove vegetation for various purposes. Local communities also persistently hunt the native camelid species for food – vicunas and guanacos – which now are in short supply. (These practices contrast sharply with our experiences of those in similar grasslands in neighboring Argentina, which protects such animals but also extends social services to the local populace. Herds of vicunas and guanacos can readily be observed in northwest Argentina.)

The surrounding mountains of the puna valleys are bare towards the peaks and covered in tall grasses on lower slopes. Everywhere there are terraced fields marching up steep slopes nearly to the tops of the mountains, centuries old techniques of potato farming, which appear to have been largely discontinued in recent times. Active terracing – which involves entire communities – is still practiced in some areas, however. It is not possible to identify the types or richness of habitats that existed on mountain slopes before human exploitation by pre-Colombian civilizations. Suffice it to say that few areas remain unaltered.

In lieu of cultivation, many Andean communities have turned to raising livestock in the grasslands. Cattle, sheep and the most destructive of hooved animals – goats – can be seen in many puna areas. These practices ensure that the grasslands will not recover after several generations of disuse. Native camelids have soft pads on their feet that reduce the impact on native grasses. Domesticated animals (other than alpacas and llamas) damage puna grasslands with their hooves, as well as by their grazing methods.

Video of Indio discussing the overuse of Grasslands:

The non-productivity of puna grasslands in sustaining indigenous communities has led to massive migration to the suburbs of major cities like La Paz and Cochabamba, and even to Santa Cruz and the lowlands of the Amazon basin. These movements complicate efforts to conserve forest resources, as further explored below.

Puna photo highlights below:

Yungas and Cloud Forests. As we descended the high mountains, magnificent Yungas forests decorated the lower slopes of the mountains. Based in the resort town of Coroico, we experienced the transition between Amazonian and Andean habitats. Amazon habitats quickly gave way to Yungas forests as we ascended (and survived) the Camino del Muerte (literally the “highway of death”), whose name is anchored in prior times when the road was the only highway between La Paz and the Amazon lands to the north. The unpaved “highway” is posted with tributes to the many departed motorists and truck drivers, who perished by falling to certain death over the 1000-ft drop-offs that still characterize the roadside. The good news (at first glance) is that the road traverses a magnificent stand of Yungas forest, beginning with drier forest edging above Amazonian vegetation and continuing to higher elevation cloud forest, periodically shrouded in mist and exhibiting numerous tree ferns, which abruptly appeared to demarcate the cloud forest.

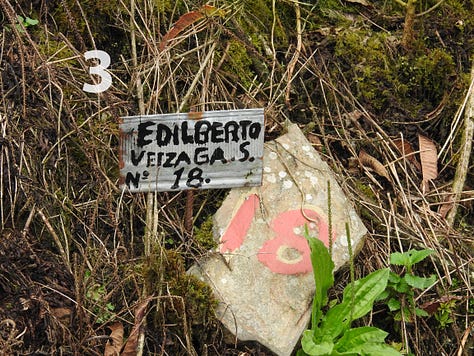

But the highway’s name persists, no longer for its reputation as a graveyard for human folly, but for the death of the forest itself. The lower Yungas forest now is subject to the invasion of claim seekers, empowered by the government’s programs for “land reform.” Under these laws (or practices, it is not clear the extent to which legislation regulates what formerly would have been called squatters’ rights), settlers can acquire title to a plot of land by converting it to “productive use.” In practice, this means clearing the forest completely for farming. We witnessed several recent claim stakes along the death highway, easily recognized by the charred remains of fallen trees and not yet in “productive” use. The fire engulfing one parcel obviously had gotten out of hand, evidenced by a scar of burned land extending far up the slope of the mountain. Visible from the road in the distance were other cleared tracts ready for cultivation, completely surrounded by intact forest.

Evidence of “land reform” was not confined to the Department of La Paz. Several days later we visited Yungas cloud forest east of Cochabamba that was similarly beset by colonists seeking to gain title to forest plots by indiscriminately clearing forest. As our guide Emiliano confirmed, the land at the entrance to a rough road and occupied by pristine forest two years before now was a wasteland of dead trees. The settler’s family was with him, his young daughter giggling amidst the roar of chainsaws finishing the preparation for a house and farm plot. Further along the road, more forest land had been converted to subsistence agriculture. The natural wonders of the cloud forest were still present, as a large feeding flock of birds convened for us in the mist. For how long, we wondered.

Fate of the lower Yungas video below:

Yungas clearing on the Highway of Death below:

Our final experience of the Yungas forest was in Amboro National Park above the historic resort town of Samaipata. After lunch in the town, we drove several kilometers on the sometimes-rough road ascending the mountain to the park entrance. Tall forest at the summit harbored soaring swallow-tailed kites and a huge eagle (the Chestnut-and-Black Eagle, increasingly rare throughout its range). Then we came to a locked gate blocking passage to other sections of the park. A local rancher soon let himself out of the sequestered area, explaining to us that the ranching community bordering the park had installed the gate to prevent the further onslaught of claim seekers, who had already cleared land in preparation for acquiring title under the government’s land reform laws. Although the cleared parcels were part of the national park and enjoyed nominal protection, once the land was occupied by settlers, we were told that the government would not dispossess them.

Yungas photo highlights below:

Tree Ferns signal cloud forest video below:

Cloud forest La Siberia video below:

Video of Indio on the importance of cloud forests below:

Video of the majesty of Yungas cloud forest below:

Cleared land in cloud forest. Video below:

Fate of the cloud forest. Video below:

Cloud forest photo highlights below:

TInter-Andean Valleys. Bolivia’s second largest city, Cochabamba, lies in a narrow valley between towering mountains. The valley floor has long been cultivated and the slopes above the town are home to indigenous [group name] farming communities. Cochabamba gives a first impression of a quiet, former colonial city, with many parks and tree-lined boulevards. Beneath this façade, however, lies the festering hostility of indigenous communities toward ruling economic and political elites. In 2010, such sentiments erupted into violent protests over water rights. Dubbed the Water Wars and memorialized in a fictional account in the film Even the Rain, the conflict left many dead in the streets and the central part of the city destroyed.

Headquartered in the city center, we ascended Cerro Tunari that towers over Cochabamba and the top of which is now a national park, for a very productive morning of roadside birding. The road abuts a beautiful river – at this time mostly dry – and traverses dense shrubs and a forest of medium height trees. The vegetation at higher elevations changes to polylepis forest, trees that recall the madrones of the western U.S. This habitat, threatened throughout the Andes by clearance for agriculture and as fuel for firewood, is critical for sustaining high elevation wildlife.

While we scanned the river from a bridge mid-way to the summit, we were confronted by a leader of the local farming community, who insisted we had failed to obtain his permission to use the public road and that we had to immediately leave. After a heated argument with our guide, he stomped off to urge local authorities to confiscate our equipment. Fearing violence, we moved on to the polylepis forest protected within the national park and took lunch at a summit lake much reduced by continuing drought. (A recent report estimated that Bolivia has lost as much as 45% of its surface water during the 10-year ongoing drought). The incident reminded us of the continuing hostility of many local communities toward outsiders they encounter in officially public areas, which they regard as a threat to their sovereignty over the land.

Inter-Andean valley habitat video below:

Video from above Cochabamba Cerro Tunari road below:

Indio on the importance of the transition zone. Video below:

Indio on high mountain lake water loss. Video below:

Non-native trees above Cochabamba. Video below:

Cultivated land above Cochabamba. Video below:

Photos highlights from above Cochabamba below:

Several days later we descended to another dry Andean valley cut by the Rio Mizque. The river runs through desert-like vegetation resembling chaparral and interspersed with many kinds of cacti. Of international importance, it is home to the endemic and critically endangered red-fronted macaw. These large parrots were persecuted by local farmers because of their habit of ravaging crops and were also victims of international bird trafficking. But there is a good conservation story here. The macaws’ roosting cliffs adjacent to the river were purchased by Asociacion Armonia with assistance from other NGOs. A small ecolodge was established across from the high cliffs. As we can personally attest, this is a spectacular venue that affords breathtaking views of the macaws and several other parrot species.

Rio Mizque Valley photo highlights below:

Lowlands of the East. Our journey to the lowlands of the Department of Santa Crux began at Refugio Los Volcanes, a private eco-resort bordering Amboro National Park and containing several types of lowland forest that surrounds towering sandstone peaks (non-volcanic, the name notwithstanding) in the foothills of the eastern Andes. The site is bisected by a clear stream and contains numerous trails passing through the habitat of many forest species. The forest, however, was eerily quiet, the birds mostly silent, and the sky full of dense smoke. We initially thought the fires originated in the eastern grasslands, where farmers and ranchers burn grassland in advance of the onset of the rainy season beginning in October.

To the contrary, 10,000 hectares of forest was burning on the slopes of the Andes many miles distant from Santa Cruz. Air quality plummeted in this metropolis of 2 million people, we were to discover as we entered the city two days later, forcing the closing of schools for 4 days. As reported in the media, the source of the fires was an indigenous community engaged in clearing land for agriculture. Whether the fires were deliberately ignited on a wide scale, or whether they resulted from out-of-control local burns, was not known at the time. What was known, however, was that the community prevented police and firefighters from entering the area to control the fires. This appeared to us as another example of underlying hostilities that lead to destruction of valuable forest resources.

Los Volcanes photo highlights below:

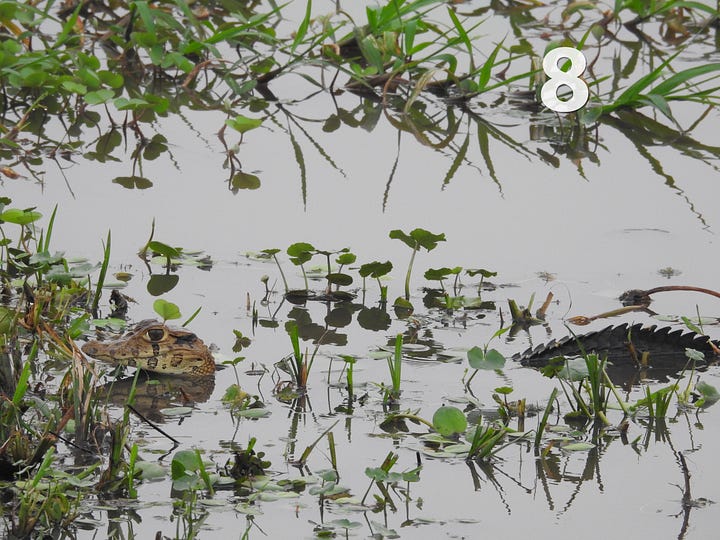

The last stage of our journey commenced in smoke-filled Santa Cruz, where we caught a plane to Trinidad, the capital of the department of Beni in northeastern Bolivia. The objective was another macaw refuge established by Armonia in the seasonally flooded savanna known as the Llanos de Moxos. Barba Azul (“blue beard,” referencing the throat pattern of the macaw) as the site is known protects the nesting and foraging grounds of the endemic blue-throated macaw. The plummeting population of this large parrot also has earned it the status of “critically endangered” and for reasons much the same as those affecting its cousin the Red-fronted Macaw. The eco-lodge usually is accessible only by charter flight from Trinidad.

On our charter flight to Barba Azul, we could see meandering rivers (the largest of which is the Marmore, a tributary ultimately flowing to the Amazon), oxbow lakes and gallery forests north of Trinidad that transitioned into vast seasonally flooded grasslands peppered with “islands” of palm forest. Once at the refuge, we were treated to a spectacle of water birds, including many species of North American shorebirds that overwinter in the wetlands of the llanos. The magnificent blue-throated macaws were overhead at times, sharing the skies and the fruiting trees with the even larger blue-and-yellow macaws. The chest-high yellow grasses (awaiting the greening of the rains) were home to a declining species, the cock-tailed tyrant which we were fortunate enough to encounter in some numbers.

This refugio is just that. The endemic Blue-throated Macaws exist in few other places. The land surrounding the refuge is bordered by cattle ranches depleted by overgrazing. We met two young Danish researchers tasked with documenting the difference in wildlife numbers on the refuge and on adjacent ranch land. While it is obvious from the air, given that there is little vegetation left on the ranches, scientific confirmation is always welcome. Protecting the refuge from huge, Zebu cattle from adjacent ranches and the semi-wild domestic pigs that forage its territory at night is a constant job for refuge employees.

Video of seasonally flooded savanna, Llanos de Moxos below:

Llanos photo highlights below:

Analysis: Possible Solutions to Biodiversity Threats in Bolivia

Two overriding principles that govern this analysis must be stated at the outset. First, there is no universal grid that can be used to evaluate biodiversity threats, nor are proposed solutions universal. Macro-economic, social and political factors differ significantly from country to country. For example, the population pressures in many African countries like Angola fuel biodiversity loss much more than they do in Bolivia. So too does the role of governments. Strong governmental oversight in some countries contrasts sharply with the total lack of enforcement of environmental laws in other countries.

Second, one must approach the subject of solutions with great humility. A short visit to Bolivia provides many more questions than answers concerning effective strategies to counteract biodiversity loss.

That said, the biggest single threat to biodiversity that we were able to observe directly was the clearance by fire of Yungas forests by settlers supported by government land reform laws, policies and practices. We can easily deduce that in practice at least, land entitlement is not constrained by requirements that the use of the land be compatible with forest regimes or even promote sustainability. As such, there is no limit to the amount of deforestation that can transpire under current governmental policies.

While it is tempting to say the solution lies simply with placing conditions on land conversion that further forest conservation, coupled with rigorous enforcement measures, that suggestion ignores the political realities of Bolivia. (Conditions are easy to articulate: limit the amount of forest clearance by a percentage of the size of the plot; restrict clearance of adjacent plots; plant only crops that can grow in forested environments such as shade coffee.) For centuries indigenous peoples have been dispossessed of communal lands, leading to the hostilities that emerged even on our brief visit toward anyone appearing to be associated with past exploitation. Self-governance runs deep in the socialist fabric of the current Bolivian government. Thus, there is little incentive to restrict the creation of new indigenous settlement patterns to conserve forest land that is valued at zero in the context of social justice.

The situation is complicated by the country’s internal migration patterns. La Paz is ringed by the sprawling suburb of El Alto, whose population now exceeds that of the central city, with no end to the growth in sight. Markets characteristic of highland communities line the streets of El Alto, interfering with efficient transportation movements. As noted earlier, agricultural productivity in the puna highlands cannot sustain the communities that traditionally have lived there. Highlanders (appearing anomalous) can even be seen in the streets of the eastern lowland city of Santa Cruz. Prolonged drought exacerbated by climate change undoubtedly drives such migration trends. Promoting settlement of forested areas serves as an inexpensive political safety valve to otherwise volatile indigenous grievances.

What can be done? There are conservation organizations in Bolivia that have succeeded in protecting sensitive habitats, such as the refuges that Armonia has established for endangered macaws. Armonia is the Bolivian partner of Birdlife International, whose objectives are to document threated bird populations worldwide and define a system of important bird areas (IBAs) by country that guide national and local efforts to preserve the habitats of such species. [https://www.birdlife.org/] In Bolivia, a considerable amount of research has been performed by biologists and field ornithologists to track the geographic distributions of bird species. This database, which can be overlaid on habitat types serves as the basis for some of Armonia’s projects.

One drawback to focusing on the preservation of IBAs is that some are narrowly drawn to protect critical habitat for one or two species of birds. That could be said of the two macaw refuges. How broader-drawn IBAs can be preserved remains to be seen, particularly in areas like the Yungas, where wide-spread clearance is underway. The success of the macaw projects may be in part due to the relative undesirability of the land that was preserved for other commercial purposes (cliffs in dry valleys, overgrazed grasslands in the savanna).

Another approach that bears consideration is the development of eco-lodges in community-held or controlled lands. A good example of this was undertaken in Maddidi National Park, the largest in Bolivia, by a Quechua-Tarcana community. The community constructed two lodges at different elevations in the park, supported by an extensive network of trails to provide access to the forests. Chalalan Ecolodge (https://chalalan.com/en/) is located in the Amazon and Sadiri Lodge (http://sadirilodge.com) is located in foothill forest on an outlying ridge of the Andes. Such projects need to be supported with patronage (and donations), since they preserve large tracts of forested land in different habitat zones and funnel badly needed funds to local communities. It is especially important to create a project in the wet Yungas and cloud forests, as none exist now.

The quest for scale must be a part of any serious attempt to conserve forest land in Bolivia. One outcome of the recent COP 28 gathering in Dubai was recognition of the importance of forest conservation as a tool in the fight to control carbon emissions. It was accompanied by a pledge among countries to preserve 30% of forest land by the year 2030, echoing the pronouncements of the COP 15 conference on biodiversity. Conference members also recognized the importance of resources-rich nations designating large tracts of forest as protected reserves. However, there was also recognition that governments worldwide were under pressure to release reserved lands for settlement or exploitation, and that the borders of nominally preserved land were being eroded by settlers and commercial interests of every sort. From our brief experience this phenomenon is progressing in Bolivia’s national parks and reserves.

Is Bolivia ripe for carbon trade agreements, by which large carbon emissions producers purchase the right to preserve forest and savanna land that consume an equal amount of carbon? Progress is being made in measuring just how much carbon can be absorbed by forests and savannas. A recent study utilizing satellite data concluded that such absorption was being underestimated by as much as a third. On the other side of the ledger, the carbon footprint of an emitter can be measured with increasing accuracy.

Bolivia has many relatively large national parks and forest reserves. The great advantage to putting such land under a carbon trade agreement is that a new source of funding can be procured for definition and enforcement of protected status and for supporting community involvement in the preservation process. (While COP 28 established a fund by which developed nations contribute to developing countries’ adaptation to climate change, no rules are yet in place for how such funds will be distributed. It seems likely that infrastructure projects will consume the lion’s share of this funding source.)

The utility of a carbon trade agreement in preserving biodiversity depends on how funds are apportioned among government entities and affected communities. The use of carbon trade funds for local communities affected by forest preservation is a matter of great importance and must be carefully structured in the agreement. If programs for clearance and settlement of Yungas forests are to be phased out, for example, then alternatives must be identified and funded under the agreements. Much work remains to be done, but carbon trade agreements should be considered as a means of preserving large tracts of forest in Bolivia.

Our transect included the high Andes grasslands north of La Paz surrounding Lake Titicaca, the largest natural body of water in South America and the highest large lake in the world; the spectacular Yungas forests of middle elevations, dry inter-Andean valleys near Cochabamba, and seasonally flooded grasslands and savannahs in the lowlands of the Beni Department.

I hope you have enjoyed this presentation on Bolivian biodiversity. The principal focus of Saving Terra is the appreciation and protection of biodiversity in tropical countries. In the near future, we will discuss beautiful Thailand and the challenges to biodiversity being faced there. I invite you to join me on my journeys. Consider subscribing to Saving Terra here on Substack and contributing to the dialogue regarding effective conservation programs by commenting on this essay or via any of our social media channels. Saving Terra, the podcast will be debuting in 2024 and will include discussions with people from around the world doing their part. You can also join us on adventures via Instagram and Twitter. We look forward to having you along.

T.D.

About TD

T.D. (Terry) Morgan is a cli-fi author whose extensive travels around the globe studying and observing the effects of climate change on biodiversity combined with his background as a former land use and property rights attorney, serve as inspiration for his novels. Click here to explore TD’s books

T.D. and his wife, Karen, began their international travels, oriented around wildlife observation in the mid-80’s venturing into Central America, South America, Africa, Asia, and Antarctica with an eventual focus on the world’s rainforests and the African savannah and have since visited all 7 continents finding birds, story ideas and ways to support individuals and organizations working to restore planetary biodiversity.

T.D. was inspired to write his first novel, Tarangire Dreams, after a trip to Tanzania observing the family life of African elephants and the vital role they play in maintaining the savannah ecosystem. Tired of the soft solutions approach to anti-poaching campaigns, main character Will Jordan, a retired American land rights lawyer and ex-Special Forces officer recruits a team of retired professionals turned adventurers to disrupt the ivory poaching trade within Tarangire National Park.

His second novel The Wrong Client is set in Texas, Brazil and Argentina in the year 2034 with the earth passing 1.8 degrees Celsius setting off a global warming emergency never faced before. Russian espionage, a below-the-radar- Antarctica research team and a potentially deadly trip down the Amazon tributary dot this climate fiction and legal thriller while highlighting the threats to humanity and biodiversity posed by sea level rise, tropical deforestation, and perhaps the most incipient of all, greed.

When not out in the field, Morgan and Karen spend time between their home in Dallas, Texas and at their ranch in southeast Arizona.

Photo credits: Karen Walz

Biodiversity in Bolivia Bibliography

Birdlife International, Important Bird Areas Americas: Bolivia [https://datazone.birdlife.org/userfiles/file/IBAs/AmCntryPDFs/Bolivia.pdf]

Birds of Bolivia: Ecological Regions [https://birdsofbolivia.org/birding-in-bolivia-2/ecological-regions/]

Cabezas, S., The hidden crisis of deforestation in Bolivia [https://globalcanopy.org/insights/insight/the-hidden-crisis-of-deforestation-in-bolivia/]

Convention on Biological Diversity, Bolivia (Plurinational State of) Main Details [https://www.cbd.int/countries/profile/?country=bo]

ESPA, Amazonia-Yungas Observatory on Biodiversity and Indigenous Health and Well-being: Development of a South-South-North research and partner consortium

Forests News, Challenges and Opportunities for the restoration of Andean forests [https://forestsnews.cifor.org/51493/challenges-and-opportunities-for-the-restoration-of-andean-forests?fnl=en]

Forests of the World Bolivia [Birds/Bolivia/Forests%20of%20the%20World%20-%20Bolivia.pdf]

Herzog, S., Terrill, R. et al, Birds of Bolivia Field Guide (2019: Asociacion Armonia)

Miller, R, Pacheco, P., Montero, J.C., The context of deforestation and forest degradation in Bolivia, published as Occasional Paper 108, Center for International Forestry Research (2014)

Ecologi, Protecting and restoring Andean Forests in Bolivia [https://ecologi.com/projects/restoring-andean-forests-in-bolivia]

NACLA, Bolivia: The Unfinished Business of Land Reform [https://nacla.org/blog/2013/3/31/bolivia-unfinished-business-land-reform]

Pelligrini, L. and Dasgupta, A, Land Reform in Bolivia, the Forestry Question, in Conservation and Society 9(4), 274-285 (2011)

SDSN, The impacts of deforestation on biodiversity in Bolivia [https://sdsnbolivia.org/en/the-impacts-of-deforestation-on-biodiversity-in-bolivia/]

USAID, Bolivia Tropical Forestry and Biodiversity Assessment (2008)

Washington University, Mountain High [https://source.wustl.edu/2021/04/mountain-high/]

World Bank, Poverty and Equity Brief Bolivia [https://databankfiles.worldbank.org/public/ddpext_download/poverty/987B9C90-CB9F-4D93-AE8C-750588BF00QA/current/Global_POVEQ_BOL.pdf\